Quote Me on That: The Proper Use of Quotations in Journalism

June 14, 2024

The main task of a journalist is to tell a story, and a great story always involves people.

If you’re writing any sort of article, even a company blog, you are effectively a journalist. Like any good journalist, you’ll find value in interviewing experts for your pieces. That will involve getting quotes from the person you’re interviewing, and that’s not as easy as it may sound. In fact, a lot of writers make errors when using quotations.

Whether it’s an article in a newspaper or magazine or something researched for a blog post, a journalist uses quotations to bring feeling, insight, and opinion into a piece—the human element. With the use of quotations comes a great deal of responsibility.

Quotations can do a lot of heavy lifting in a story. They make a story compelling to read, or insightful, and even add a great deal of drama. One of the important things the use of quotations does is to characterize the individuals involved in the story. It’s part of journalistic integrity to represent people accurately and fairly.

Naturally, as any good writer knows, mastering the use of proper quoting refines your writing skills and gives you credibility. To begin, there are several kinds of quotes you can use.

What is a direct quote?

In journalistic writing, you’ll frequently be reporting on people—from here on we’ll refer to those people, and in particular the ones you quote, as sources.

A “direct quote” is a piece of text that represents the exact words that a source spoke or wrote. Frequently, especially in the case of formal interviews and press conferences, the source will be speaking (maybe even quickly!), so it’s important to record their words accurately. Whether note taking or audio recording, the journalist needs to record, to the best of their ability, exactly what a source says.

If you’re conducting an email interview, all the text a source offers will be right there on your screen, so it’s easier to tease out great quotes. It’s also easy to ask for clarification.

How long should a direct quotation be? In terms of working a direct quote into a piece, the shorter the better.

One to three sentences is typical for a direct quotation, though there are instances where you might use more. The idea, though, is concision. Find the pithiest quotes.

Though it goes without saying—or should—a direct quote is signified by using quotation marks, which will contain the exact words of the source between them. Use punctuation to show the readers that someone is speaking—don’t make them guess.

Note that there are also indirect quotes, which means to paraphrase something the speaker or writer said. In an indirect quote, we do not use quotation marks.

Why use quotes, whether direct or indirect?

There’s a difference between facts and feelings, between common knowledge and individual opinion. A good story should have all of these.

The writer has a lot of facts to keep straight and is responsible for arranging those facts in the writer’s own words. But facts, as journalists often describe them, are often “dry,” even dull. Stock market numbers, sports scores, the dollar amounts of damage done by a flood: These are all facts and, as such, are common knowledge. You don’t have to quote common knowledge, even when conveyed by a source.

If you’re writing a business blog, there will be technological news, economic trends, and so on—things that just happen. Anyone can report on those, but the story is enriched by how we as people respond to those happenings. That’s where sources come in.

So, when is the best time to use quotes?

When To Use Quotes

Try these:

1. When you want to record what comes directly from human beings: their opinions, emotions, and unique expressions on a subject.

“If you want to be a rock star or just be famous, then run down the street naked, you’ll make the news or something,” said Eddie Van Halen. “But if you want music to be your livelihood, then play, play, play and play! And eventually you’ll get to where you want to be.”

2. When a source offers a distinctive clarification of a topic or makes a promise or even prediction of some sort.

“Investors should continue to be on the lookout for opportunities in the market and consider taking advantage of the stock market’s recent pullback, where many quality stocks went on sale,” Clark Bellin told Forbes.

3. When it’s colorful, intriguing, and memorable; dramatizes the situation; and characterizes your source as someone truly interesting and important.

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously said.

4. When an indirect quote, a paraphrase, or a source’s statement can be conveyed better by yourself as a writer.

For example, as CNN reported on Miss America Noelia Voigt: Voigt said she was proud of her work with Smile Train, a nonprofit that provides corrective surgery for children with cleft lips and palates, as well as her advocacy for anti-bullying, dating violence prevention and immigration rights and reform.

Quotations add authority. Not only is the quoted or paraphrased source an authority on the subject you’re writing about, quoting them demonstrates that you the writer have authority, as well: You know where to look for the best information, which is to say, you’re the writer who has done their homework. You know what’s memorable or mundane, and the difference between them.

Attributing Sources Properly

While the journalist is thinking about quotes, they should also be considering the personality of the source themselves: Why are they worth listening to? Importantly, what is the source’s authority? Why can we depend on what they think, feel, and imagine? Are they credible?

A source’s authority is expressed in the attribution. First, provide the source’s name. When a source is mentioned for the first time, you need to give their full name, first and last. After that, and particularly if they’re an adult, you need only refer to them by their last name. Sometimes that person will be relatively unknown, and other times they may be “Bill Gates.”

Name alone won’t always convey the importance and authority of your source. Their title (or their occupational description) will be an important detail. If you’re writing about a corporation, knowing that the person being quoted is the “CEO” will obviously give them authority and credibility, but even “officer,” “senior editor,” or “doctor” will work wonders, depending on the subject.

As a reference, when using a job title, you do not capitalize it unless it is the first word in a sentence or when it precedes a person’s name, like “President Roosevelt,” but remember he’s only one of the many “presidents of the United States.”

Attribution, in short, shows the reader how close your source is to the action, how much they understand the issue or event, and why we should pay attention to what they say.

How to Construct a Direct Quotation

Quotation marks are necessary to signify a direct quote. Other rules generally apply, as well.

When you’re writing your sentences, there is a standard pattern to documenting a quote: quotation, attribution, verb. Start with the quote, follow with who said it, and use a generalized verb like “said.” For example, here’s a quote from a story published by NBC News on the Olympic torch that was recently lit in Paris:

“The Olympic flame has been a symbol of peace and friendship among nations since antiquity,” the International Olympics Committee said.

That style is standard. Here’s another version, from the same story:

“In these difficult times we are living through, with wars and conflicts on the rise, people are fed up with all the hate, the aggression and negative news they are facing day in and day out,” IOC President Thomas Bach said in a speech at the ceremony.

In this example, notice the attribution: This is the International Olympics Committee (IOC) President speaking, and therefore he’s important. We also get a sense of the context: This was spoken at the “ceremony,” where a “speech” suggests the formality of the occasion.

The writer can follow other best practices. First, don’t bury the attribution; that is, don’t make the reader wait to see who said a quote. If you’re using a lengthy quote, break up the sentence so you can insert, earlier on, the attribution.

Here’s an example of “not burying the lead” from a story in the Washington Post, the interviewee being Captain John Konrad, founder of a shipping news website:

“Our ports are vulnerable,” said Konrad, who was the first to report on the Qingdao incident in New York. “America has to decide—do we want to invest in vessel traffic service, stronger bridges, better maritime Coast Guard investigators? Or do we want to roll the dice?”

Compare that to this version:

“Our ports are vulnerable. America has to decide—do we want to invest in vessel traffic service, stronger bridges, better maritime Coast Guard investigators? Or do we want to roll the dice?” said Konrad.

See the issue? It takes too long to get to the who.

Second, don’t use unnatural breaks in the quote. For example: “I’m,” he said, “leaving.” Let the breaks follow grammatical structure: “I’m leaving,” he said, “and I’ll be back tomorrow.”

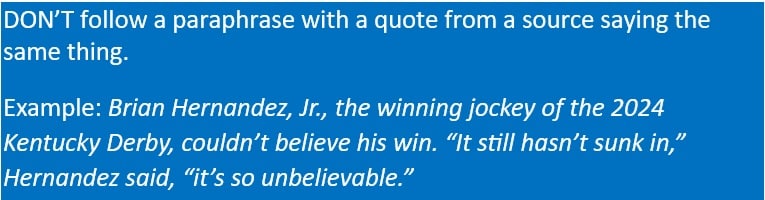

Finally, don’t repeat yourself. The meaning in any paraphrase you write should not be “echoed” in a quote. Remember, if it’s easier and more expedient to paraphrase, then do that as a writer.

Four Types of Quotes

There are different quotes for different occasions.

1. A full quote will convey everything a source said. It can be as simple as a full sentence. For example: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country,” President John F. Kennedy famously said. (Think, complete sentence.)

2. A partial quote is one in which part of the original quote is omitted. A common use here is a smaller phrase, or even a single word from a quote, that is unique to the point where it’s difficult or even impossible to paraphrase. The entire sentence from a source may not convey the power that a few given words from it do.

Here is an example from CNN, quoting basketball player Caitlin Clark, who collaborated with Prada:

Ahead of the draft, Clark called her collaboration with Prada “pretty special,” in a red-carpet interview (though, technically, said carpet was orange-colored) with the WNBA.

Or this partial quote, reported by the Associated Press:

Hugh Grant received “an enormous sum of money” to settle a lawsuit accusing The Sun tabloid of unlawfully tapping his phone, bugging his car and breaking into his home to snoop on him, the actor said Wednesday after the agreement was announced in court.

Partial quotes can often bring out the best of a quote and make it flow nicely with your own writing.

3. A lead comment not only opens a piece, it practically launches it. For example, here’s a lead quote from a CNN story on the Columbia University president’s testimony on antisemitism before a House committee (note that it has elements of both a partial and full quote):

Claire Shipman, co-chair of Columbia University’s board of trustees, said it is “difficult and heartbreaking” to hear members of the university community feel unsafe.

“I feel this current climate on our campus viscerally. It’s unacceptable. I can tell you plainly that I am not satisfied with where Columbia is at this moment,” Shipman said. “As co-chair of the Board, I bear responsibility for that.”

A lead quote is used because the quote itself is dramatic and makes for a strong, emotional opening.

4. A kicker quote sums up a story or report by offering an emotional ending that sticks. This quote ends the story.

Another story from NBC News reports on unscrupulous telemarketers who claimed to be “tax service specialists” during COVID that snared small business owners desperate to keep their businesses alive during shutdowns. The story begins with Scott Volner, a Missouri business owner who was duped, and ends with a quote from him:

“I feel betrayed, because I think I was sucked into it,” he said.

There’s a decidedly human element here, a sentiment that drives the point home.

Much of the drama of a piece is due to how you weave the quotations throughout to achieve an effect. Think of it like a symphony—that is, you can make a blog a literal work of art.

The Do’s and Don’ts of Quotations

With all that in mind, here’s a list of general rules for using quotations correctly in journalism, whether for the New York Times or for a company blog. Lots of sources online—like Bobby Hawthorne, Dennis Jerz, and Roy Peter Clark offer good advice; some of it is distilled here:

- Overall, use quotes sparingly. A single quote can carry a lot of weight and, regardless, the main job of telling a story goes to you, the writer. Don’t rely on quotes. As an article from Texas A&M’s University Writing Center says, “using too many direct quotations obscures your voice.”

- Punctuate correctly. The punctuation, especially quotation marks, makes it clear that you are using a direct quote. Without them, the reader assumes it is a paraphrase.

- Don’t summarize a quote before you introduce it. Let the quotation itself do the work, and trust that the reader will get your point.

- Avoid transitions into the quote. Some examples: “When I showed up at the White House to meet the president, he said…” or “During the press conference, when he was asked about the economy, the senator took a sip of his water and then replied…” Just jump to the point.

- Say specifically if a quote comes from an email or a written text. Email, especially, can be used for interviews with busy people—and email interviews and conversations are common now—but be clear with your readers if this was the case.

- Intersperse quotes throughout a piece. Don’t clump them together.

- Give full quotes a full paragraph. Full quotes get their own paragraph, whether a full sentence or several. Look at news stories online, and you’ll see how this works.

- Don’t overuse partial quotes, as it can begin to seem like you’re leaving things out, which can be construed as being manipulative and, worst of all, putting words in someone’s mouth. That costs you credibility right away.

- Only use a lead quote if it is absolutely amazing. Generally, the lead paragraph is used to offer a quick synopsis of the story, but if a quote does that to strong effect, use it.

- That said, try to place a quotation early in the story. That means allowing the reader to make a connection to another human being quicker.

- To avoid errors, make an audio recording of an interview. Today, a smart phone can easily make an audio file, and there are transcription apps to get all the words into text. Having an audio file also protects you from misusing or making mistakes with quotations.

- Clean up. You can edit the quote for clarity. Unless they’re giving a prewritten speech, not everyone speaks clearly on demand, and so there are likely to be stop’s and start’s, pauses, interjections, or just the occasion “umm.” You can clean this up, and if you think it might be distorting the actual quote, contact the source for clarification.

These are a few of many tips, and they come with experience and practice.

One of the easiest ways to develop a style of your own that incorporates quotations and sources is to read. Read a lot.

Creative writers know this: They learn their own craft by reading and analyzing the style of the writers who write well, if not excellently.

To be a good journalist, read good journalism, not just blogs. With practice, writers working on company blogs will begin to feel more like journalists and reporters than just content creators.

I said it earlier, but it bears repeating: With good use of quotations, any writing can be a work of art.