Is Traditional Publishing Still Worth It?

March 30, 2017

“Writing a novel is like driving at night in the fog,” E.L. Doctorow once said. “You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

It’s a complex issue, full of facets and trade-offs. The choice depends on who you are, what you’ve written, and what you want your book to achieve. No answer is right for every author or even for every book from the same author.

So which way do you go? This blog examines some of the factors you might want to consider.

The Basic Question

First ask yourself: Is there an issue at all? Do your readership and goals make the choice clear?

You likely want to self-publish if:

You expect a narrow audience. If you are writing for your family or a niche readership, you may have no choice. Traditional publishers won’t risk funding for tiny audiences. One exception: books for academics or professionals like lawyers and financial analysts. In these cases, publishers anticipate few sales but real demand, so they raise prices, often to the hundreds of dollars.

You have a brief piece, such as a novella. Traditional publishers rarely publish such works.

Your readership already knows and follows you. If you have a built-in audience, most potential buyers will know of your book, and you can sell directly to them.

Self-publishing is the norm in your field. Indie publishing predominates in some areas, like romance and erotica. In 2016, for instance, 55 percent of romances were self-published. Indie is also common in science fiction and fantasy. Readers in these genres are so familiar with this approach that the traditional route may be pointless.

You need to publish quickly. Meg Xuemei X self-publishes paranormal romances like The Empress of Mysth, and she notes that romance authors may write a book every two months, or even every month. Readers await these works and consume them quickly. Print publishers are pachyderms in this world of hummingbirds.

You want a traditional publisher if:

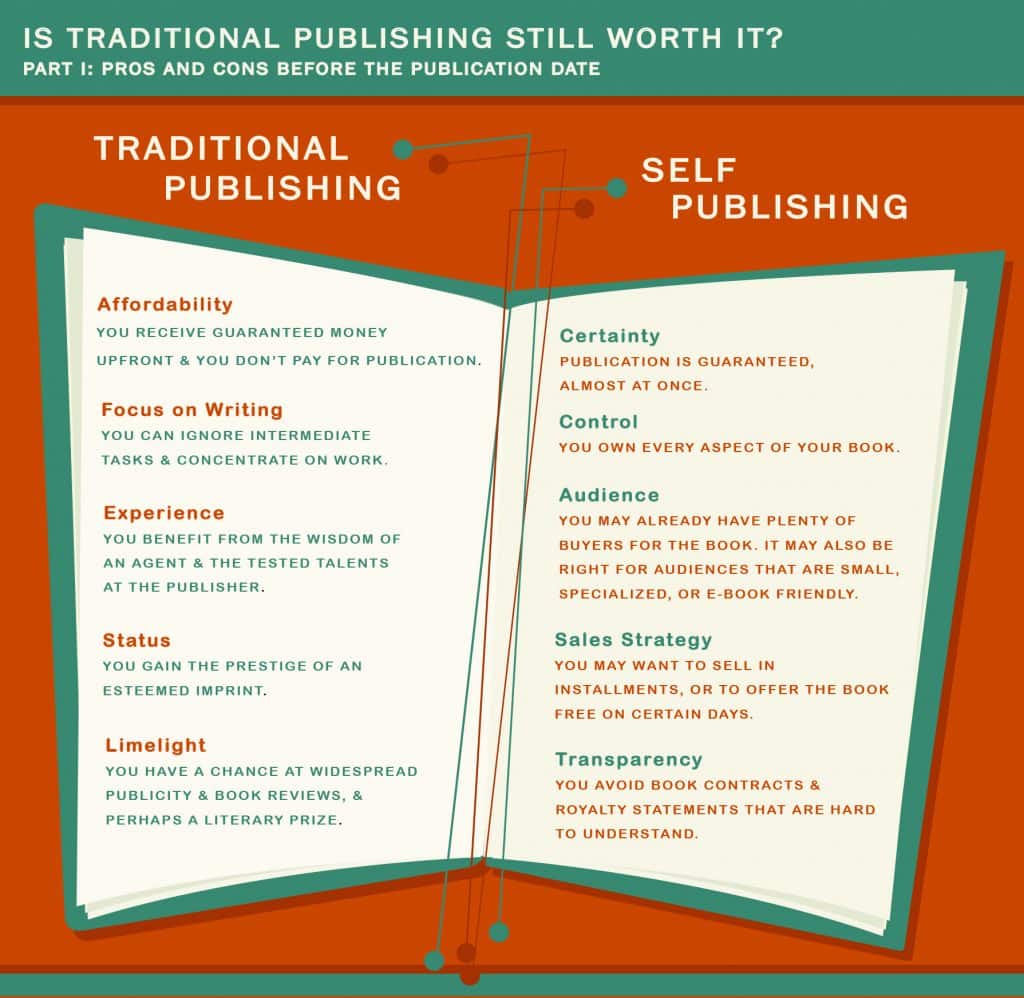

You need an advance. If you’re writing nonfiction, traditional publishers may give you money upfront, based usually upon just a proposal with a book outline. You typically get a third of the advance at the outset, and it can make your book possible.

You want a guaranteed fee. You get to keep the advance even if you don’t sell one copy. The publisher retains your percentage of sales until that running total exceeds the advance, and then you start getting royalties.

You don’t want financial risk. You pay nothing for editing, cover, and book design, much less printing and distribution. In self-publishing, you run the risk of losing money.

You want broad publicity, especially if you dislike marketing. Traditional publishers have the power to get radio and TV interviews for you, as well as book reviews in major papers. blogs, and periodicals. They certainly expect you to do marketing, but they take on key burdens themselves. With self-publishing, it’s different. “Marketing is a beast, but a necessary one,” says Alexes Razevich, author of such indie novels as Khe and Shadowline Drift. “Unless someone stumbles onto your book, loves it, and tells their millions of friends, the independent author is going to be doing it all on their own.”

You want acceptance by a famous name. Traditional publishing can confer automatic prestige. If, say, Random House publishes your work, everyone knows you have passed through strict quality filters. If you self-publish, your book can be anything; you have to cultivate prestige yourself.

You seek literary awards. For these, you almost have to issue the book with a traditional publisher.

Traditional publishing is the norm. It remains de rigueur in areas such as literary, children’s, and academic books.

Beyond these questions lies a realm of greater subjectivity. It falls into two categories: The Search and Control.

The Search

Your search can fall into two categories. If you want a traditional publisher, you usually have to get an agent, who then has to get a publisher. You’re selling your work, and you’re competing with lots of other sellers, at both stages.

If you’re self-publishing, you may need to find people who can create covers, and illustrate book design, and perhaps do marketing. But they want to sell their work to you.

You may want to self-publish if:

You hate rejection. If you’re new, and sometimes if you aren’t, you can expect serial rejection from agents and publishers. J.K. Rowling is not the only best-selling author who has run this gauntlet.

That’s one reason Harper Lee advised aspiring writers to grow a thick hide.

But understand that rejection letters aren’t the same as verdicts. Send out a query, and it doesn’t go to an all-wise judge. It goes to a human being. Agents and editors live in a river of submissions and must make snap judgments. They know that you’ve put sweat and soul into the book and that they may be passing on a best seller. So “rejection” can mean many things: The person reviewing your work is already too busy…didn’t connect subjectively…had a bad day…or spotted a typo in the query letter. If you understand the context, you may feel less like Kafka’s K. waiting outside the castle. But hearing “Sorry, not for us” repeatedly may still be painful. If so, you may prefer self-publishing.

Your book is a genre mashup. Indie publishing is the great experiment garden of books, and crossovers have flourished. “Where traditional publishers might have a problem assigning an imprint for a ‘vampires in space meets steampunk’ told from the point of view of a teenage boy and his talking dog,” Razevich says, “independent publishers simply put it out there, and if the story was well told and the book professionally presented, readers will find it and buy it.”

You want to be sure of publication. With self-publishing, you have a publisher who adores your book. So you can write with the confidence that others will see it. It won’t lie unread in the hard drive, perhaps to vanish in a crash.

You may want a traditional publisher if:

You don’t like DIY. Though it’s easy to find independent contractors, you do have to search for them. You may prefer simply to write.

Control

“The joy and whole point of being an independent publisher is doing it the way you want,“ says Razevich. But there are also drawbacks to this power, and if that power matters less to you, you may prefer a traditional publisher.

You may want to self-publish if:

You want to fully own your book. You can determine everything: cover, book design, font, price, marketing copy, time to publication, release date. No editor will pressure you to change the title, say, or the plot. And since you dictate price, you can use deft marketing strategies (such as offering the book free for a day) to boost overall sales.

A thriving infrastructure now supports self-publishers. For instance, a print-on-demand site like Amazon’s CreateSpace offers tools for you to create covers and design the book. You can let it handle every aspect of the process or just the parts you select. For instance, you might want to farm out the cover to a graphic designer you know. Regardless, you’re at the helm.

In contrast, a traditional publisher may exert serious pressure over, for instance, the title. You are in a partnership with the company, and it has an interest in the sales. But the pressure can go too far. Best-selling author Daniel McNeill says the major houses he has dealt with have been very reasonable. But he knows of one small press that imposed petty rules like banning “since” to mean “because.” Why? “Since” might also be referring to back in time.

You don’t mind the upfront costs. Self-publishers pay for all the stages of the book process themselves. “The costs of several rounds of editing—I do three rounds—can be daunting, but it’s worth every penny,” Razevich says.

You fear the contract might be a minefield. A traditional publisher requires a contract, for obvious reasons. But unless you have a reliable track record, you have less bargaining power. It’s a harsh reality, but you want them more than they want you. So the contract terms typically slant against you.

In addition, you probably lack experience with contracts themselves, as well as knowledge of which provisions are standard.

One author, whose name we are withholding, signed a deal with the e-publishing arm of a respected house and wound up ceding all rights to his characters forever. He didn’t have an agent, and a good agent can usually prevent these problems by keeping the deal to common standards.

But even with a savvy agent, contracts are relatively inflexible—and they favor the publisher. They can also hide surprises. McNeill says, “I’ve seen clauses that say, ‘The author will provide advice and counsel on the cover.’ Then they’ve sent me the cover and said, ‘We love it. What do you think? Our deadline is in two hours.’” To be fair, publishers don’t want endless input from authors they deem ignorant about selling books. And McNeill notes that he has offered cover advice that editors have followed gratefully. Your relationship with the publisher is a living thing. Yet with indie publishing, the cover is exactly what you want.

You want to publish in installments. Traditional publishers issue books as, well, books. They don’t come out in portions, since readers haven’t wanted to go to the bookstore regularly to get installments. But the Internet makes it easy. Moreover, our world has gotten much faster: attention spans are shorter, and people are used to briefer pieces of information. You may also earn more—overall—by issuing a book in parts.

You may want a traditional publisher if:

You’re comfortable handing off the tasks. Publisher pressure may not bother you.

You want the benefit of experience. If you’re just venturing into the world of publishing, you may make amateur errors. And the more you control, the more errors you may make. But traditional publishers are in the business full-time, and some have been for decades. With the traditional route, you can benefit from their wisdom.

Traditional publishers not only take care of most publication needs, but they also have tested professionals on staff. For instance, they may know better than you which covers will sell. McNeill wrote a work called Fuzzy Logic, and Simon & Schuster issued it with a cover that said “FUZZY LOGIC” in big red block letters. It wasn’t pretty, but you could see the title halfway across the bookstore, and McNeill noticed browsers coming over to check it out. It worked.

On the other hand, mistakes are inevitable when learning any process. You learn by committing them. So you shouldn’t avoid self-publishing just because you may make mistakes. They’re just little halts on your journey. The biggest mistake is not to try for fear of mistakes.

Thank you very much. Very useful.