How to Conduct Research for a Successful Whitepaper

March 2, 2021

In business, whitepapers provide companies and professionals with the opportunity to communicate knowledge and share information.

To make a whitepaper truly valuable, the information contained in it must reflect careful and diligent research, which then serves as the backbone of the whitepaper’s content.

After all, a whitepaper is worthless if the information contained in it does not serve any purpose. Regardless of how good the writing is, a whitepaper does not provide value if the information is of no use to its intended audience.

Isaac Newton once said, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Indeed, research enables both writers and readers to see further thanks to the contributions of giants in their respective fields. Hence, writing a whitepaper is about systematizing such contributions into a format that delivers valuable insights in just the right dose.

Whitepaper 101

When written effectively, a whitepaper can become a highly valuable source of information. Reputable organizations use whitepapers to raise awareness on a specific issue.

Most importantly, a whitepaper is about presenting a solution to a particular challenge or problem. As such, a white paper provides the opportunity to expand upon a given issue or challenge.

A whitepaper is simply an authoritative document containing the information presented by a company or non-profit organization to raise awareness of a problem and offer a potential solution.

For companies, whitepapers generally serve as a marketing tool to present a problem of interest to their customers and then introduce products and services to alleviate the situation.

In the case of non-profit organizations, whitepapers shed light on a specific issue, generally as a means of fundraising.

Government agencies may also publish whitepapers as a means of informing the public on a specific matter. The whitepaper would contain information about the particular issue and then provide guidelines, action plans, or recommendations to influence public opinion on the subject.

Types of Whitepapers

In general, there are three main types of whitepapers: the Backgrounder, Numbered List, and Problem/Solution. Each one corresponds to a specific approach intended by the organization publishing the paper.

According to the Corporate Finance Institute, “…white papers are now being used commercially as a document for marketing and sales. They are also prominently used in the field of technology to discuss the potential uses of a new product and how it can help increase the efficiency of processes in companies.”

This statement underscores the importance of whitepapers as marketing tools. Thus, each type of whitepaper serves a specific marketing purpose.

The Backgrounder

To begin with, organizations use the Backgrounder to inform the public about an issue. Then, the organization can propose a solution.

Companies can take advantage of the opportunity to present a new product or service as the solution to the problem presented.

The Backgrounder does the following:

- Presents data, papers, and research to support claims

- Informs on why their solution is the best

- Positions the brand as the leader in its respective industry

Consequently, the Backgrounder is useful when providing general information while touting the solution with as many credible claims as possible. Often, companies use this type of whitepaper as a sales funnel.

The Numbered List

The Numbered List is similar to a standard blog post format, such as “Top 5 Reasons Why Whitepapers Are Important.”

This format allows companies to present their reasons in a logical form. As Megan McKenzie at Crowd Content points out, titles such as this “…help reframe information in a way that’s less intimidating, and, if you’re up to it, fairly entertaining.”

While a whitepaper’s purpose is to inform and not entertain, making it engaging to readers helps boost the paper’s popularity.

Like the Backgrounder, each item on the Numbered List should be full of credible sources that can back up claims. Of course, there is room for opinion. However, opinions should stem from reasonable evidence and quantitative data.

The Problem/Solution

The Problem/Solution is the most potent whitepaper format as it presents a problem with the organization offering its solution for the problem. It is worth noting that this type of whitepaper does not seek to instill fear in the target audience. Instead, its purpose is to create awareness of a problem. Then, the organization can present its solution.

This type of whitepaper is the most effective kind when it comes to promoting products or raising funds. When done appropriately, it can create a great deal of concern on the issue, thereby compelling readers to act.

In the words of Megan McKenzie:

“Whether you’re looking to change public opinion, build a following, enhance your sales and marketing plan, generate new leads, or carve out a place in your industry, a problem/solution white paper could be exactly what you need to shake up the status quo and establish your authority.”

Indeed, compelling readers to act is the ultimate goal of any quality whitepaper.

The Importance of Research

There is no question that research is the backbone of any quality whitepaper.

Whitepapers that make claims without backing them up appropriately fall into the category of gimmicky marketing material. Thus, organizations must conduct their due diligence to back up their claims.

In the words of Gordon Graham, the widely acknowledged whitepaper expert, “When you’re searching for white paper sources, any company can claim they’re the best. But finding the evidence to prove that can be tough.”

These words poignantly underscore reality. Many companies can claim their solutions are best. However, proving that to be the case is an entirely different situation.

Appropriate research is what gives a whitepaper credibility. Without it, the paper may risk being discredited somewhere down the line.

Even when its claims make sense on the surface, competitors can quickly debunk it by simply pointing at the lack of evidence to support it.

Writing a compelling whitepaper is like building a legal case. As per Gordon Graham, “When you think like a lawyer, you want to build a case so tight that no judge can question it and no jury can resist it. You need an argument so tight it leaves the other side gasping for air. That means digging up a mountain of evidence.”

Like seasoned trial counsel, white paper writers need to think about every possible angle from which the competition could attack the paper. Doing so generally requires tremendous amounts of research. When done correctly, though, competitors and critics will have very little room for rebuttal.

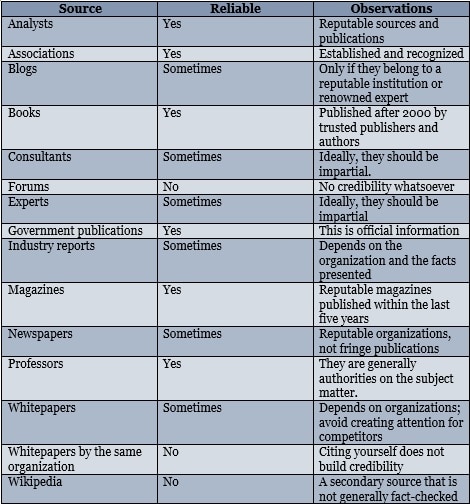

It is also important to point out that research is only as good as the sources used. According to Gordon Graham, these are the best and worst sources to consider using in a whitepaper.

Direct interviews with renowned experts or statements from official organizations can significantly impact the credibility of a whitepaper. For instance, getting government officials or notable individuals to comment specifically for the whitepaper can create an indirect endorsement of the information contained in the paper.

However, it is important to avoid celebrity endorsements unless they are recognized figures in their respective field.

Conducting Effective Research

After credible sources, the biggest challenge is conducting research effectively.

Inexperienced writers and researchers tend to hoard piles of information to the point they may find it challenging to sift through all of the information. After all, making sense of data is no easy task.

To make all that research worthwhile, whitepaper writers must consider the premise of their argument. Like a lawyer, they must build their case around a theory and then utilize the information available to prove it. There may be times when the theory is widely disputed. But if the evidence backs it up beyond a reasonable doubt, it may sway public opinion in their favor.

All three types of whitepapers must have a central premise. This premise revolves around a problem that the specific product or service solves. In the case of non-profit organizations, they must present evidence on why the issue is relevant and how their organization contributes to solving it.

Once a central premise is in place, a preliminary review of existing literature is a great place to start.

Databases like JSTOR provide access to journals and publications in a vast array of fields.

Also, Google Scholar has quickly become the go-to source for academic and scientific research. From there, whitepaper writers can gauge the amount of evidence available to support their premise. As the literature emerges, they can build their argument using the information available.

On the whole, academic databases represent secondary information. While credible, secondary information comes up short insofar as providing the first-hand experience on the specific subject. This is why first-hand knowledge can make any whitepaper extremely valuable.

First-hand information includes interviews, surveys, questionnaires, and direct observation.

According to the Ohio State University research guide:

“Primary research is often first-person accounts and can be useful when you are researching a local issue that may not have been addressed previously and/or have little published research available. You may also use primary research to supplement, confirm, or challenge national or regional trends with local information.”

When there is little to no information on a subject available, whitepaper researchers will have to go out and get it. This is what makes a whitepaper so valuable.

I addition, first-hand knowledge can provide ironclad support to claims, thereby making it impossible to debunk. A great example of this can be found in the pharmaceutical industry. Clinical trials are first-hand experiences that provide the necessary claims to support the effectiveness of a new drug.

Secondary information is also highly valuable. It is useful for reinforcing any first-hand experience. It is also widely used when obtaining first-hand information is not possible or impractical. The Ohio State University research guide has this to say about secondary information:

“Secondary research requires that you read others’ published studies and research in order to learn more about your topic, determine what others have written and said, and then develop a conclusion about your ideas on the topic, in light of what others have done and said.”

Good trial lawyers rely on expert testimony to back up their argument. As such, the judge and jury can see that if experts agree with the counsel’s assessment, they too should have reason to trust the argument.

A significant challenge when conducting research is organizing information.

Since most research is done electronically nowadays, apps such as Evernote allow researchers to organize their ideas easily. Moreover, data can be stored based on specific points. This, in turn, facilitates collecting information by storing it in notebooks for quick reference later on.

Organizing data based on specific points and topics makes building an argument much more straightforward. Supporting an argument is easier when information is collected around that argument instead of piling information together and then sifting through whatever might be useful.

Strategies for Effective Whitepapers

Photo by Gladson Xavier from Pexels

Arguably, the most influential whitepaper in history is the Bitcoin whitepaper published in 2008.

At that time, Bitcoin seemed like a science fiction concept. Today, Bitcoin is one of the most valuable commodities on the planet. The subsequent rise of Bitcoin to prominence started with its whitepaper.

In Graham Gordon’s estimation, the Bitcoin whitepaper was highly successful for four reasons:

- “It’s clear and easy to read.

- It contains facts and logic, not just opinions.

- It’s long enough to explore the topic in depth.

- It’s economical enough not to waste a word.”

In these four points, it is evident that a successful whitepaper is about getting straight to the point while ensuring the information clearly supports all claims.

While there is room to present the product as the solution to an issue, the argument must be so convincing that there can be very little room for debate.

Also, the depth of writing must be just enough to explore the topic. Herein lies the dilemma. There is no specific length for a whitepaper. This is where writing a whitepaper becomes an art. Its length should be enough to develop the topic adequately. At the same time, a paper’s length should not skimp on language. This fact highlights the need for efficient language that gets to the point. Overly inflated phrases don’t apply here. Please bear in mind that readers want to get information.

Another essential element to consider is the “Big Idea.”

A big idea is a genuinely unique contribution that the whitepaper offers. Whitepapers that rehash ideas from earlier documents tend to pass by unnoticed. While not all whitepapers may highlight a breakthrough, they should provide an angle that is innovative and even revolutionary.

The Bitcoin whitepaper exploited the idea of a revolutionary idea. And while it was ahead of its time for 2008, it signaled things to come. That is why successful whitepapers should always strive to present cutting-edge ideas as much as possible.

Whitepaper Structure

Solid whitepapers follow a similar style. Regardless of the paper’s individual style, the following structure always works well.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Discussion

- Calculations

- Conclusion

- References

Like college papers, an abstract should summarize the paper, main takeaways, and conclusions. Generally speaking, it should be about 100 to 150 words.

The paper’s introduction should then present what the paper is about, the main premise, and an overview of the paper’s contents.

In the discussion section, the paper should expand on the problem and solution. This is the point where evidence and sources need to emerge.

In the backgrounder and problem/solution papers, the discussion should essentially break up into two parts: the problem and the solution. As for the numbered list paper, each item in the list should present a part of the problem and how the solution addresses the situation.

The calculations section is ideal for presenting raw data to support the solution. This could be survey results, statistics, government data, or any other credible quantitative data that supports the paper’s claims. Additionally, financial considerations such as cost-benefit analysis, return on investment, or balance sheets should also make up this section.

The conclusion section provides a summary of the main points and takeaways from the paper. A bullet-point format is useful. Also, a paragraph-by-paragraph description may work.

Lastly, the references section should list all of the documents, sources, and individuals consulted as part of the paper’s research.

Conclusion

A whitepaper has the potential to transform the world. The Bitcoin whitepaper is a clear example of this potential. A well-researched and thought-out paper can present innovative ideas that can revolutionize an industry and even the world.

The backbone of any successful whitepaper is research. Without it, a whitepaper is nothing more than a collection of opinions and ideas that do not lead anywhere. They are like a map that takes treasure hunters around in circles.

Following a solid structure with credible sources provides a whitepaper the foundation for presenting information that compels readers to act. Moreover, it contributes to the knowledge base of its respective field.

In the words of Gordon Graham:

“There are two kinds of discontent in this world; the discontent that works, and the discontent that wrings its hand. The first gets what it wants, and the second loses what it has. There’s no cure for the first but success; and there’s no cure at all for the second.”

Indeed, a great whitepaper is a manifestation of discontent as it provides a solution to a problem in the world. Its outcome is a successful solution to that problem. When a whitepaper fails to live up to its purpose, it wrings its hands. A whitepaper could become the beginning of the end of a problem facing society. Therefore, an ironclad case, as if going to court in a murder trial, will give a successful whitepaper the chance it deserves to excel.