Copywriter Q&A: RFP Survival, Success, and Lessons Learned with Shelly Spencer

February 11, 2019

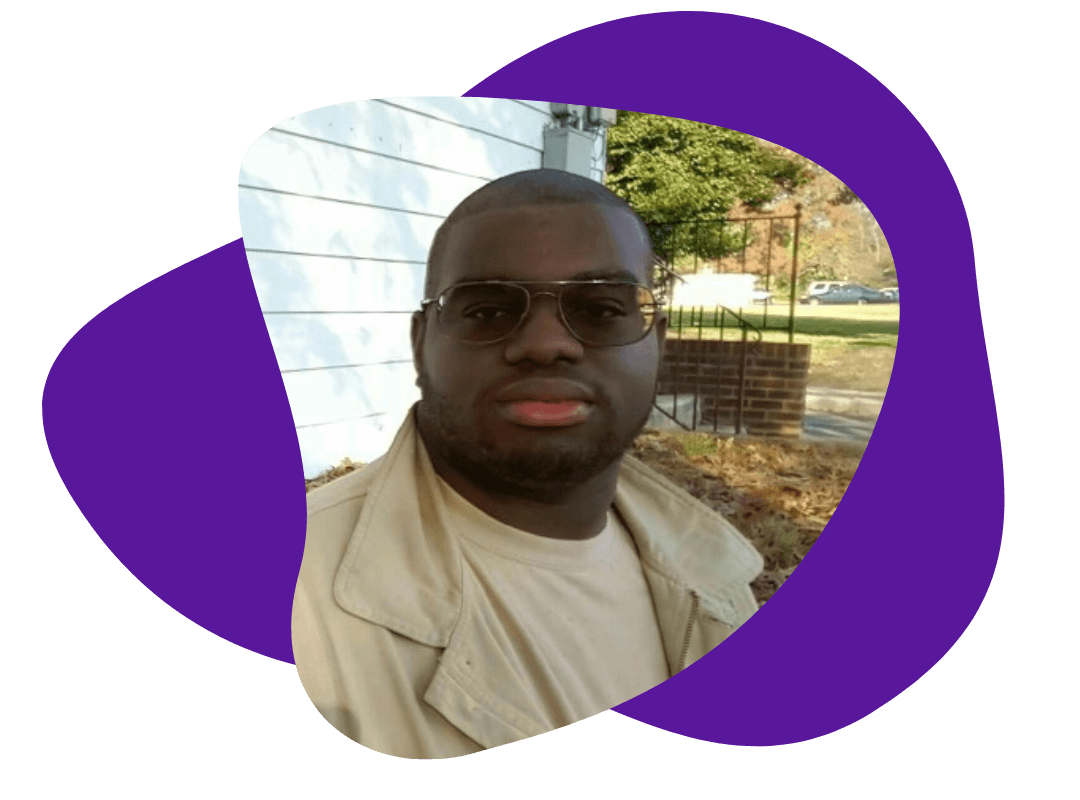

TWFH team member Shelly Spencer has more than two decades of experience in RFP writing and has worked with up-and-coming organizations and non-profits with budgets of $30 million per year. One thing she’s learned? Although RFPs can vary greatly in terms of subject matter, industry, length, and format, the process of preparing a response is essentially the same across the board — and your chances of success really come down to a few key elements.

Shelly sat down with us recently and was gracious enough to answer some of our burning questions about surviving — and thriving — as you navigate the complicated process of crafting a killer proposal.

TWFH: How long have you been writing RFPs?

SS: I started out grant writing, and that morphed into RFPs as well. I got started mid-2000s; I’ve been doing this for almost 20 years. My RFP clients were pretty much all nonprofit, although I did some for-profit as well. I liked the idea of working with nonprofits. They’re in the business of helping people, helping the community, and doing good for the greater good.

TWFH: Is there a difference between writing RFPs for nonprofits, versus other types of businesses and organizations?

SS: They’re pretty much the same. All you have to do is follow the instructions. They are usually very specific in their instructions: They require one-inch margins, 12-point font. You have to put in this format in this order, you have to title it this way.

TWFH: What is the most challenging part of an RFP response?

SS: Some RFPs have a tendency to ask the same thing in different sections, so you find yourself trying to answer all of the questions, but not in a way that sounds like you’re repeating yourself. Getting creative with that can be a challenge.

Another challenge is that some RFPs ask for very specific, quantifiable results. They want to know your outcomes and outputs, and they want a very clear understanding of what you’re going to produce. Some organizations don’t always track those things; their programs can be hard to quantify. I have one RFP client who runs a food bank, and they started a community garden where women veterans volunteer and grow crops. It’s a great program, but we had to provide numbers; the pounds of crops produced, how many people are served, how many veterans work there. They want to do good, which is great — but you also have to focus on the numbers and details.

TWFH: What are some of the most common mistakes people make when responding to RFPs?

SS: Probably one of the biggest mistakes in responding to RFPs is bidding on a project that doesn’t fit. If you’re stretching beyond what is reasonable, it’s not worth it. RFPs take a lot of time, and it can be disappointing if you get to a place where you have to say, “We just don’t fit.” But you have to be realistic. I’ve seen some clients who try to “throw a program at money” and put something together willy-nilly to fit what the RFP is looking for. Rather than, “this is what we do,” it becomes, “let’s create a program because there’s money out there.”

TWFH: What is the most misunderstood part of the RFP process?

SS: The terminology can be challenging. The instructions are there — but if you don’t understand RFP terminology, it’ll be harder to follow those instructions. Also, some people don’t realize the extensive nature of RFPs. There’s the written part, but there are also attachments, budgets, collaboration letters — all of the extra stuff that’s not part of the actual writing process. It’s easy to just peruse the RFP and say, “This is a fit for us.” But then when you get into detail and read it, you realize that there are things involved beyond writing.

TWFH: RFP responses are a ton of work, with lots of people involved, multiple moving parts, etc. What advice do you have for staying organized during the process?

SS: In the beginning, make sure to figure out who is involved: Get everyone’s contact information and find out what role they play in the process. I usually start with a kickoff meeting to discuss the project scope. Then, I do a draft based on my research, and we build on that. I have the client review it and give their input: Am I on target? What do I need to change? What am I missing? I work through it from there.

TWFH: Do you have a standard “plan of attack” for RFPs?

SS: To me, the easiest way to start is by reading the RFP. Figure out what they need. Then, I start formatting. A lot of times, they want the RFP in this order, and they want you to use these specific headings, and so on. That becomes my outline, and I can start plugging in info. Also, when a client provides information, I copy and paste it into the appropriate section, and then I highlight it so I know that it’s their wording and needs to be rewritten.

TWFH: Do you typically use a template or have “boilerplate” copy that you can use from one RFP to another?

SS: I don’t see the point in reinventing the wheel. If you have a successful proposal already done, it can be to your benefit to re-use copy. I don’t mean that you have to use everything, and you don’t have to use it verbatim, but it can be more efficient to have those standard boilerplates.

Using boilerplates in RFPS helps ensure that you're always getting the same message out. It's like branding: You always want your RFP to have the same messaging, especially if you use more than one writer. Tweet this

TWFH: What do you think is the most important part of an RFP? Is there a “make or break” section?

SS: That depends on the RFP. Many RFPs will tell you exactly what to focus on. For example, if they have a 100-point scoring system, they might weight the “background” section at 10 points, but they might give 50 points to your “scope of work” section. They’re telling you what’s important to them, which sections carry the most bearing. Make those larger-pointed sections your main focus. Make those sections sparkle.

TWFH: Are there any RFPs you have won that you know for sure what about your response made the difference between winning or losing?

SS: In so many cases, it’s the whole proposal overall. Although I did once receive feedback that that my client’s proposal was one of the best because it didn’t have a lot of extra fluff. We looked at the questions, and we answered the questions. All it takes is being concise, clear and filled with a bunch of unnecessary stuff.

TWFH: In your opinion, what do successful RFPs have in common?

SS: They fit within what it is the RFP is trying to accomplish. They follow directions. They look as professional as possible. They pay attention to the little stuff that can be overlooked: H